Information Warfare: China, Russia, and Influence Operations Involving NGOs

State and Other Actor Involvement & Support

Report Details

Initial Publish Date

Last Updated: 30 SEP 2024

Report Focus: Global

Authors: TW

Contributors: GSAT

GSAT Lead: MF

RileySENTINEL provides timely intelligence and in-depth analysis for complex environments. Our global team blends international reach with local expertise, offering unique insights to navigate challenging operations. For custom insights or urgent consultations, contact us here.

Introduction

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have long been seen as neutral entities dedicated to social good, but they have increasingly become targets and tools in the geopolitical influence operations of state actors like Russia and China. Both Russia and China have strategically used NGOs to promote their influence on the global stage. By leveraging NGOs, these countries can project soft power, shape public opinion, and manipulate political landscapes covertly. In addition to this, there are growing concerns about how state-sponsored hackers from these countries target NGOs for cyber operations, either to steal sensitive data or disrupt activities contrary to their interests. This two-pronged approach—using NGOs as influence platforms and hacking others—has become a hallmark of contemporary information warfare by both nations.

These countries have adeptly used NGOs to further their strategic interests, both by creating proxy organizations to promote state narratives and by cyberattacking those critical of their policies. Russia, for instance, has co-opted NGOs to influence energy policies and election campaigns, while China uses NGOs for international image-building and even espionage. Both nations exploit the vulnerabilities of NGOs, using cyber-espionage and disinformation campaigns to suppress dissent and manipulate global perceptions. The growing involvement of state actors in these operations demonstrates the crucial need for NGOs to strengthen their defenses and remain aware of their role in a broader geopolitical maneuvering that will include them as participants.

Russia and Influence Operations

Russia has a long history of manipulating and co-opting NGOs to further its strategic interests (or simply declaring them “undesirable”). These organizations, often positioned as charitable or humanitarian entities, are used to subtly advance Kremlin narratives, especially in regions where direct state interference may provoke backlash. Russia often establishes or funds NGOs that promote pro-Kremlin agendas under the guise of neutral or humanitarian missions. For example, Russia backed environmental organizations within the European Union to encourage member countries to abandon nuclear energy, making them more dependent on Russian oil and natural gas.

Russian-aligned NGOs have been implicated in spreading disinformation during election campaigns. They may organize conferences, seminars, or "fact-finding" missions that provide a platform for disseminating Kremlin-aligned propaganda, often painting political opponents as corrupt or illegitimate. The 2016 U.S. elections and several European elections serve as examples of how these influence operations take shape. Le Monde even found a fake Russian NGO (Facts Matter) that was part of the “Doppelganger” operation that cloned news websites to spread disinformation.

Another method is to similarly fund “media organizations” and target influencers. In September 2024, Google shut down several YouTube channels linked to Tenet Media, a Tennessee-based company implicated in a Russian disinformation campaign. This follows the U.S. Justice Department's indictment of two Russian nationals tied to RT (Russia Today) for funding U.S.-based media influencers to promote pro-Kremlin narratives, such as criticizing U.S. involvement in the Ukraine war. Tenet Media, run by Lauren Chen and her husband Liam Donovan, allegedly received over $10 million in Russian funds. The money was used to pay conservative influencers like Tim Pool, Benny Johnson, and Dave Rubin, who claim they were unaware of the source of their funding.

Benny Johnson, Dave Rubin and Tim Pool – Conservative influencers inadvertently funded by Russia. Source: NBC News

Russian Cyber Operations

Russia also targets NGOs, particularly those focused on human rights, democracy promotion, or anti-corruption work. State-sponsored groups such as APT29 (Cozy Bear) and APT28 (Fancy Bear) have been linked to cyberattacks on NGOs and think tanks, with the goal of stealing sensitive information, disrupting operations, or planting misinformation.

A recent example came in September 2024 when the Free Russia Foundation, a U.S.-based nonprofit advocating for democracy in Russia, reported a data breach after hackers published thousands of its emails and documents online. The foundation suspects the Kremlin-linked hacker group Coldriver is responsible. This breach follows a broader trend of phishing campaigns targeting human rights organizations, as highlighted by recent reports from Access Now and The Citizen Lab. Coldriver, known for espionage aligned with Russian government interests, allegedly stole grant reports and internal documents from the Free Russia Foundation. The organization sees this cyberattack as an effort to further repress pro-democracy Russians and opposition groups. The leak, comprising over 13 GB of data, was shared on a Russian-language Telegram channel, including strategic planning documents and financial records. Despite the breach, the Free Russia Foundation remains committed to opposing Putin’s regime and supporting Ukraine.

China and NGOs

Though common knowledge, Chinese spying is quite extensive throughout the world, especially in the United States. However, an often-overlooked aspect of such spying is the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as tools and targets. China’s approach to NGOs and influence operations is more nuanced but equally impactful. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has embraced NGOs as instruments of "soft power" to build a favorable global image and counter criticism of its human rights record. As RAND report notes, “China views psychological warfare [influence operations], centered on the manipulation of information to influence adversary decision making and behavior, as one of several key components of modern warfare.” For example, the CCP uses government-organized NGOs (GONGOs) to spread pro-China narratives and secure influence in international forums. These organizations, although labeled as NGOs, are directly controlled by the state. One such example is the China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture. China also employs NGOs to manage its international reputation, particularly in sensitive areas like human rights. In regions like Africa and Southeast Asia, Chinese NGOs work to downplay the CCP’s domestic human rights abuses, framing China as a leader in economic development and poverty alleviation.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute has specifically called attention to the problem of the CCP’s influence operations. Their analysis indicates that the CCP is expanding its influence by co-opting representatives from ethnic minorities, religious movements, and various business, scientific, and political groups, claiming to represent these groups and using them to legitimize its authority. This strategy is managed through the United Front system, a network of party and state agencies aimed at influencing non-party entities, including those representing civil society (see Alex Joske’s Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World to understand the complete story). The CCP’s involvement in this work is often covert and deceptive, and the system's influence extends beyond China's borders into foreign political parties, diaspora communities, NGOs, and multinational corporations. As the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC) put it, “Under Xi’s rule, China’s overseas influence activities are now more prevalent, institutionalized, technologically sophisticated, and aggressive than under his predecessors.” This included the use of NGOs to promote ideas appealing to the CCP.

More importantly, the CCP has used NGOs directly for spycraft. In August 2024, Yuanjun Tang, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Queens, New York, was charged with acting as an unregistered agent for the People's Republic of China (PRC) and making false statements to the FBI. Tang, a former Chinese dissident who fled to Taiwan and later the U.S., allegedly worked with China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) from 2018 to 2023, gathering intelligence on U.S.-based Chinese democracy activists and dissidents. According to the FBI, Tang “helped the MSS infiltrate a group chat on an encrypted messaging application used by numerous PRC dissidents and pro-democracy activists to communicate about pro-democracy issues and express criticism of the PRC government.” Tang also helped infiltrate a chat group used by Chinese dissidents. He was arrested after lying to the FBI about his activities, including access to an email account used for communication with the MSS. Tang faces charges that could lead to a maximum of 20 years in prison.

That is only the most recent example. Back in 2015, Sher Yan was arrested by the FBI in New York over allegations of bribing the former president of the UN General Assembly. According to U.S. and Australian national security officials, the CCP targeted the UN through a covert operation using NGOs as fronts to funnel illicit payments to UN diplomats. Yan is believed to have played a central role in this scheme, and what it shows was the willingness to use NGOs for funneling bribes. Then in 2022, a Chinese police station in Lower Manhattan, run by the NGO America ChangLe Association NY Inc., was linked to spying on Chinese nationals in the U.S. The non-profit operated the station above a noodle shop, which was part of a global network of over 100 similar offices ostensibly meant to help Chinese nationals with ID renewals, but was actually involved in malicious activities such as spying, harassment, and forcibly returning dissenters to China. Safeguard Defenders, a human rights group, reported that these stations engage in intimidation and repression of Chinese diaspora members, and have contributed to forcibly returning over 200,000 overseas nationals to China. This is an interesting example because it was an NGO that alerted authorities to clandestine criminal activity by another alleged NGO.

Members of the Fuzhou Police Overseas Chinese Affairs Bureau. Source: NY Post

Chinese Cyber Espionage and NGOs

Meanwhile, Chinese cyber operations target NGOs that oppose the CCP’s interests or are perceived as threats. Chinese hackers frequently target NGOs, particularly those involved in advocacy related to human rights, Tibet, Xinjiang, or Taiwan. Groups like APT41 and APT10 (Stone Panda, Red Apollo) have conducted cyber-espionage campaigns aimed at NGOs, stealing internal communications, gathering intelligence on global activists, and disrupting NGO operations critical of the CCP. Organizations advocating for Uyghur rights, Tibetan independence, or democratic freedoms in Hong Kong are prime targets of Chinese cyberattacks. For example, An incident from 2023 included the APT Daggerfly targeting a U.S. NGO that operated in China, though the threat intelligence group investigating the matter did not disclose which organization it was. In early 2024, the leaked documents from I-Soon demonstrated how China has targeted NGOs, especially those connected to dissidents. Mathieu Tartare, a malware researcher at the cybersecurity firm ESET, has directly linked I-Soon to the Chinese-hacking group Fishmonger, an APT that targets NGOs and think tanks in Asia, Europe, Central America, and the United States.

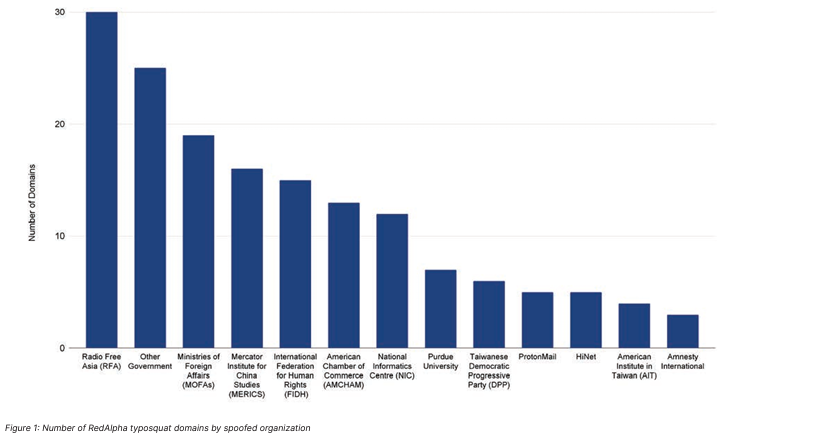

A Chinese-linked hacking group called RedAlpha conducted a multi-year espionage campaign targeting governments, NGOs, think tanks, and news agencies. RedAlpha, identified in 2018 by CitizenLab, is believed to have links with Chinese state-owned enterprises and military research institutions, pointing to its role as a proxy for the Chinese government. The cybersecurity firm Recorded Future reported that since 2019, the group has focused on stealing login credentials from organizations of strategic interest to Beijing, such as the International Federation for Human Rights, Amnesty International, Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party, and India’s National Informatics Centre. RedAlpha used credential-phishing attacks, sending emails with malicious PDFs that redirected victims to fake login portals to steal credentials. The group’s targets include Taiwan-based entities and human rights organizations, likely for intelligence gathering on democracy, ethnic, and religious minority groups. The group exploits human vulnerabilities, such as weak passwords, and takes advantage of organizations slow to adopt multi-factor authentication.

Source: RecordedFuture

Impact for NGOs

NGOs play a critical role in civil society through defending elections, offering humanitarian aid, providing education, and any number of other social and moral goods. However, that is precisely what makes them valuable targets for influence operations, manipulation, and even hacking. Typically, NGOs are more trusted that governments or even the media because they are dedicated to the improvement of society, which means malicious actors can use them as covers for their nefarious activities. In addition, NGOs often have on-the-ground information that is extremely valuable to intelligence agencies and security organizations. Russia and China have adeptly integrated NGOs into their broader influence operations while simultaneously exploiting the vulnerabilities of non-state actors in the cyber domain. Their strategies involve both the creation of proxy NGOs to promote state narratives and the use of cyberattacks to undermine or infiltrate organizations that challenge their geopolitical ambitions.

Russia and China’s hacking of NGOs can be viewed as a subset of their broader cyber-espionage and influence operations. NGOs are attractive targets because of their involvement in policy advocacy, human rights activism, and their access to political or corporate networks. NGOs are often under-resourced in cybersecurity, making them vulnerable to state-sponsored attacks. These attacks serve several purposes. By hacking NGOs, Russia and China can gain access to internal communications, research, and strategies that might undermine state goals. For example, NGOs investigating corruption or human rights abuses in these countries hold valuable information that the state wants to suppress or monitor. Cyberattacks on NGOs can also disrupt their operations, preventing them from carrying out missions that are critical of the state. This includes disabling websites, stealing donor lists, or defacing online platforms to spread disinformation. The goal is to sow distrust and make it difficult for these organizations to function effectively.

In the face of these evolving threats, it is crucial for NGOs, particularly those involved in politically sensitive areas, to bolster their physical and cyber security defenses and be aware of the broader geopolitical contexts in which they operate. Additionally, the industry must remain vigilant in identifying and countering the covert use of NGOs for influence operations by state actors like Russia and China. Influence operations and cyber espionage are linked concepts within the strategies of information warfare used by great powers to achieve their interests and promote their world views, and NGOs are piece of that puzzle.

On-Demand Expert Analysis : Request Support

Leverage RileySENTINEL's expert team for deeper analysis and tailored insights:

- On-demand consultations with our global network of advisors

- Custom reports focused on your specific operational contexts

- Proactive risk mitigation strategies for volatile environments

- In-depth analysis of regional stability factors and future outlooks

- Expedited response options for time-sensitive inquiries

Click this link to be redirected to the support request page.

© 2024 RileySENTINEL. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without prior written permission from Riley Risk, Inc.

© RileySENTINEL. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without prior written permission from Riley Risk, Inc.